Published on July 13, 2024

by SEGM

Original: Reality’s Last Stand – WPATH Influence Undermines WHO’s Transgender Guidelines

WHO’s inclusion of WPATH leaders involved in suppression of evidence sets a troubling context for the WHO effort.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reaffirmed its plans to issue a transgender and gender diverse (TGD) clinical practice guideline. Its prior announcements generated significant public concern from various stakeholders: clinician groups, LGBT groups, and parent groups. These groups raised three key issues (all of which remain unresolved).

The heavy representation of members of WPATH on the GDG has always been a concern, but this concern has now been increased by a new development. New evidence has emerged that two prominent WPATH members involved in the production of the WHO guidelines were directly involved in suppressing unfavorable evidence.

First, the WHO guideline development group lacked intellectual diversity, with most members firmly committed to the notion that hormones should be widely available to all who want them. Second, WHO decided not to review the evidence for benefits and harms for hormones and their alternatives, instead focusing on the question of how best to promote widespread availability of cross-sex hormones. Third, women’s rights advocates have noted that the mandate of the GDG includes promoting self-identification of gender in legal settings (the so-called “self-id laws”) and expressed concern that this will allow biological males unrestricted access to private spaces which should be reserved for women and girls.

In June 2024 WHO attempted to address concerns over the lack of balanced perspectives in its guideline development group (GDG) by adding six more GDG members to the group. Even with these additions, however, the GDG remains unbalanced and heavily influenced by transgender activist groups. No changes to their methodology have been made, and the scope continues to be wide, conflating medical and legal issues. As we outlined previously, if these problems remain unaddressed, the guidelines that WHO intends to produce will be seen as a politicized effort lacking in credibility.

The heavy representation of members of WPATH on the GDG has always been a concern, but this concern has now been increased by a new development. New evidence has emerged that two prominent WPATH members involved in the production of the WHO guidelines were directly involved in suppressing unfavorable evidence related to the availability of cross-sex hormones in the process of creating their society’s official guidelines: WPATH Standards of Care 8 (SOC8). Since the availability of cross-sex hormones is a key topic for the upcoming WHO guideline, this sets a deeply troubling context for WHO’s current efforts.

In our most recent response to WHO, we expressed our renewed concern with the WHO GDG composition in light of the documents disclosed in a U.S. court case, which reveal that WPATH undertook explicit steps to suppress and manipulate evidence in the space of transgender health. The brief summary of our concerns and their implications for WHO’s credibility, should it proceed with the plan, are presented below.

WPATH Suppressed Its Evidence Reviews on Hormone Use

The new evidence emerged in the case of Boe v. Marshall, which is a case brought in the United States Federal Court to challenge Alabama legislation restricting medical gender transition in those under 19 years of age. WPATH is not a party to the litigation but the Attorney General for Alabama argued that since the plaintiff was relying on the WPATH SOC8 as its primary evidence that hormones and puberty blockers were medically necessary, WPATH should produce all of the documents relating to the creation of SOC8. Some of these documents have now been unsealed and they disclose serious ethical and scientific lapses on the part of the WPATH leadership.

The court documents reveal that WPATH leadership was “caught on the wrong foot” when two systematic reviews of evidence regarding endocrine interventions, which WPATH had commissioned from an evidence evaluation team at Johns Hopkins University, did not provide the kind of support that WPATH was hoping to see. Consequently, WPATH leadership, including two prominent members who are part of the current WHO initiative, took action to prevent the evidence evaluation team from making public the offending systematic reviews.

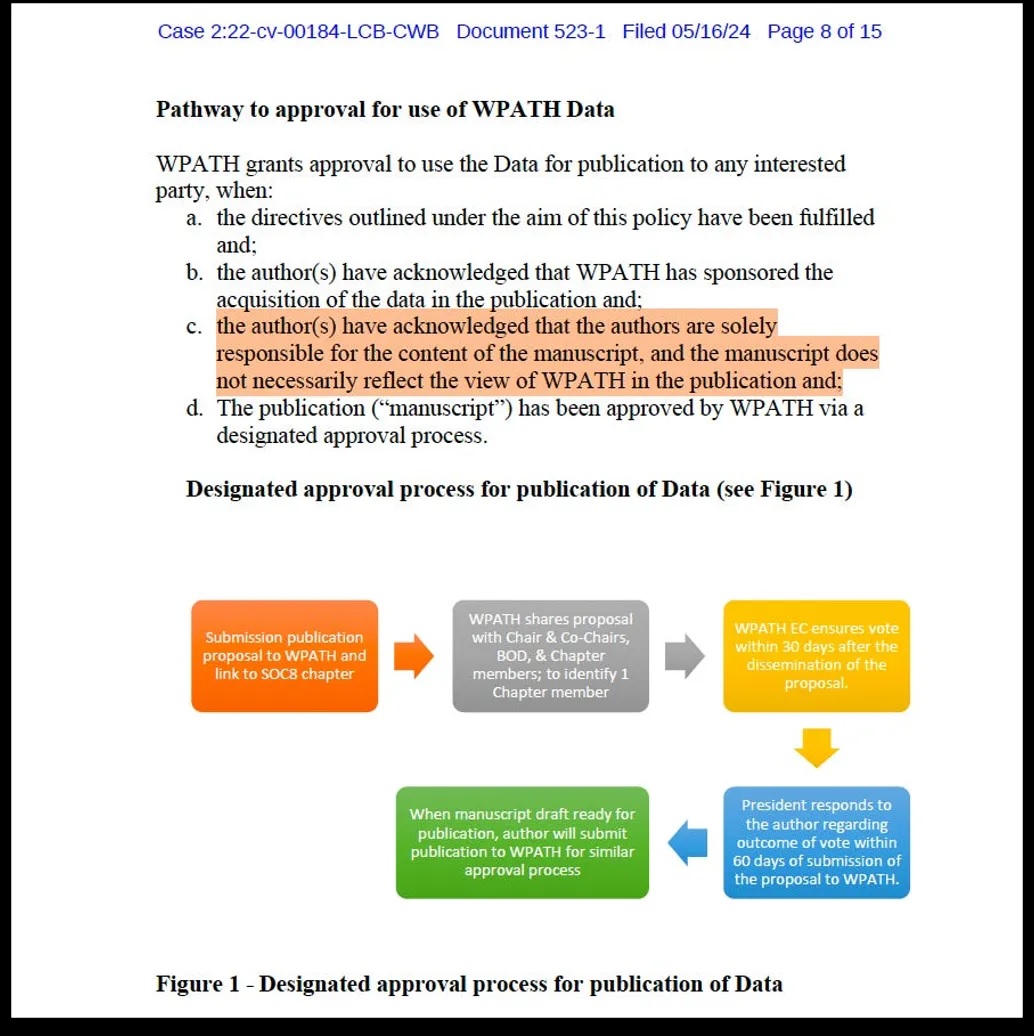

The court documents also reveal that WPATH subsequently instituted a new approval policy to ensure that only favorable evidence reviews could be published by researchers engaged in evaluating the evidence.* Any publication of the evidence reviews had to go through three rounds of WPATH interference:

- WPATH had to approve the conclusions. WPATH instituted a publication proposal mechanism which had to list the research conclusions. The “proposal” had to be approved by WPATH via a 60-day voting process, primarily to ensure the content would reflect WPATH’s views (“advancing transgender health in a positive manner”). This process kept any research with unfavorable conclusions from ever being turned into a publishable manuscript, while also sending the researchers a strong message: any uncertainty in the findings must be turned into positive framing to gain approval for publication. (This is indeed what happened to the only evidence review the survived the policy, as we detail below.)

- WPATH had ongoing content control over the content of the planned publication. While the publication was supposed to be produced by independent researchers to lend it credibility, WPATH’s approval policy required that WPATH members had to be included in the design and drafting of the content (“involve the Work Group Leader of the Chapter or, alternatively, a designated representative of that specific SOC8 chapter, or alternatively the Chair or Co-Chairs of the SOC8 in the design [and] drafting of the article”).

- WPATH had the final document control. The final draft had to be re-submitted for another WPATH vote (“when manuscript draft ready for publication, author will submit publication to WPATH for similar approval process”) and the authors had to seek explicit permission to submit the manuscript in its final form to a peer-reviewed publication.

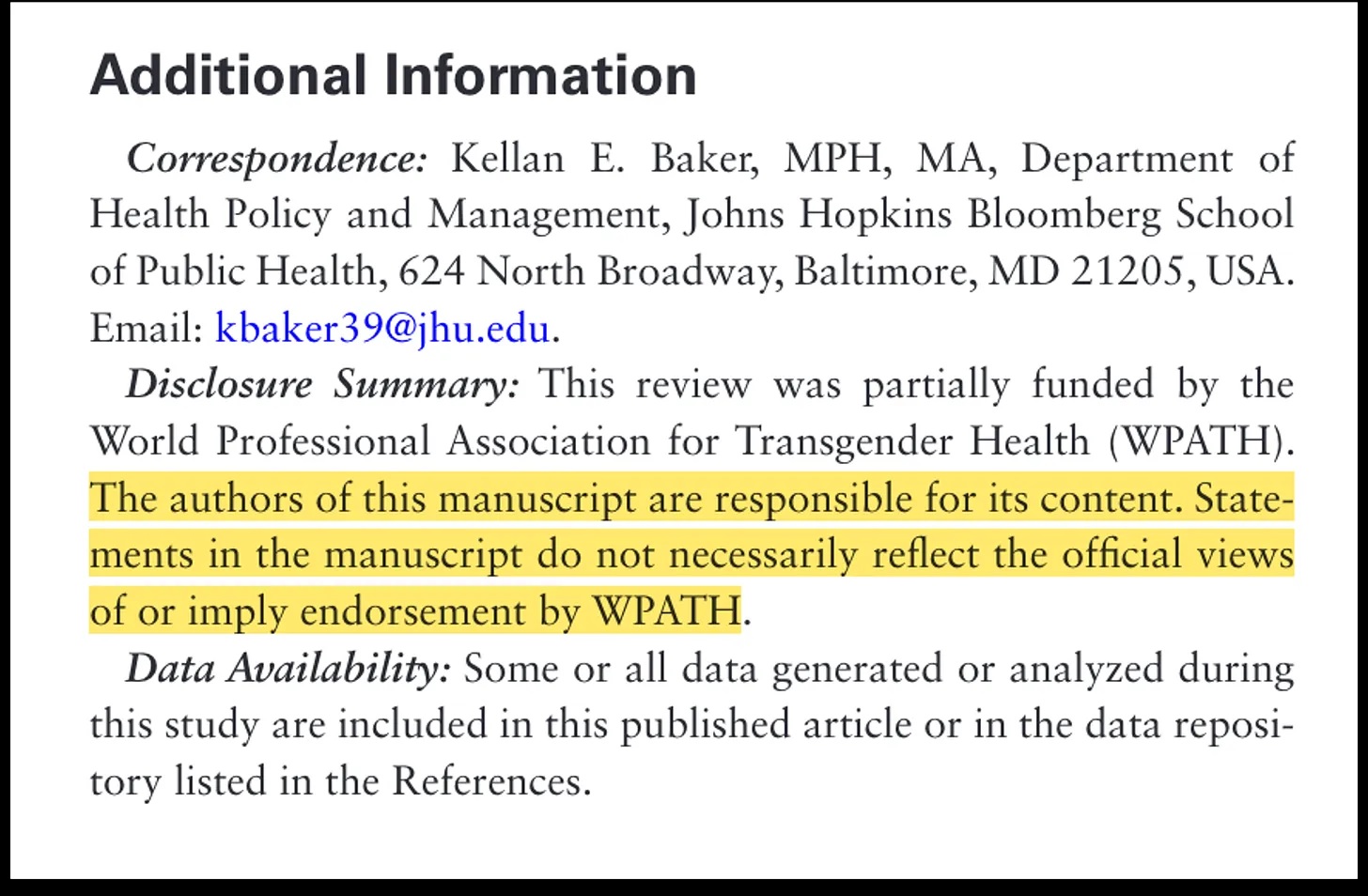

The authors were also required to insert into the article a statement that asserted its independence from WPATH, effectively denying that WPATH interference had taken place. The approval checklist stated, “the author(s) have acknowledged that the authors are solely responsible for the content of the manuscript, and the manuscript does not necessarily reflect the view of WPATH in the publicatiom.”

The WPATH Interference Is Apparent in the Published Reviews

Only two reviews in total were published. One evidence review was published before the policy change (Wilson et al., 2020). After the policy was implemented, only one other review appeared, Baker et al., 2021. It was the only review to survive WPATH’s approval process, despite “dozens” of reviews being completed by the Johns Hopkins team, as the court documents reveal.

The Baker review has an alarming number of irregularities, which bear the marks of WPATH interference, and which deserve a separate spotlight. Here, we will only note that the review’s conclusions, which were positive about the effects of hormones on mental health, are explicitly contradicted by the actual systematic review findings, which found only “low” and “insufficient” evidence. The court documents show that the Baker review went through the WPATH approval process, all the way to inserting WPATH’s required disclaimer that its approval process had not taken place.

“Dozens” of Unpublished Reviews Represent Significant Publication Bias

Publication bias is the choice to not publish the results of a study on the basis of the direction or strength of the study findings. The court documents reveal publication bias at scale. The evidence evaluation team from the Hopkins University (JHU) completed “dozens” of systematic reviews back in 2020. The reviews were completed for the following chapters: Assessment, Primary Care, Endocrinology, Surgery, Reproductive Medicine, and Voice Therapy.

E-mail exchanges show that Admiral Levine specifically requested WPATH to remove the age limits from SOC8 because they might be harmful to the government’s political agenda.

Specific to the endocrinology section (the focus on the WHO guideline), the court documents reveal that while the JHU evidence evaluation team completed the review of the evidence for a total of 13 questions (registered by the JHU research protocol for SOC8), only three of 13 questions appear to have been addressed in any published systematic reviews associated with SOC8. This indicates that the evidence reviews concerning as many as 10 remaining questions related to the use of hormones—including questions about the effects of estrogen on the risk on pulmonary embolism, deep-vein thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction (KQ5 below), and the effects of testosterone on on uterine, ovarian, cervical, vaginal, and breast pathology (KQ6 below)—remain unpublished, presumably, because their conclusions did not meet the WPATH requirement of positively “affect[ing] the provision of transgender healthcare in the broadest sense.” Examples of other questions the answers to which remain unpublished are, “what are the effects of hormone therapy on fertility and metabolic syndrome” (KQ12-13), and many others.

The 13 questions registered by the JHU research protocol are reprinted presented below, along with the current status:**

- KQ1. For transgender women, what are the safety and efficacy of androgen lowering medications compared to Spironolactone vs cyproterone vs GnRH agonists in terms of surrogate outcomes, clinical outcomes, and harms? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ2. For transgender adolescents, what are the long term effect of GnRH agonists compared to no treatment, in terms of surrogate outcomes, clinical outcomes, and harms? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ3. For transfeminine people on gender-affirming hormone therapy with estrogen, what are the comparative risks of prolactinomas and hyperprolactinemia between spironolactone, cyproterone, and GnRH agonists, in terms of prolactin levels and presence of prolactinomas confirmed by imaging? (addressed in Wilson et al., 2020).

- KQ4. For transgender people, what are the effect of progesterones (cyproterone) compared to Medroxyprogesterone and other progesterones in terms of breast growth (adults), delay of puberty (children), and side effects? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ5. For transgender women, what are the comparative risks of different regimens of gender-affirming hormone therapy with estrogens (conjugated estrogen, estradiol, ethinyl estradiol) in terms of pulmonary embolism, deep-vein thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ6. For transgender men, what is the risk of polycythemia among transgender men on gender-affirming therapy with testosterone, as measured by hematocrit and hemoglobin levels? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ7. For transgender men, what is the effect of testosterone therapy on uterine, ovarian, cervical, vaginal, and breast pathology in transgender men who have not had a hysterectomy or oophorectomy? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ8. For transgender women what is the effect of estrogen therapy on breast, testicular, prostate and penile tissue in transgender women who have not had a gonedectomy? [sic] (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ9. For transgender women, what is the safety of different routes of administration for estrogen (oral, cutaneous, intramuscular) in terms of myocardial infarction, stroke, deep-vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ10. For transgender adolescents, what are the effects of suppressing puberty with GnRH agonists on quality of life? (addressed in Baker et al., 2021).

- KQ11. For transgender people, what are the psychological effects (including quality of life) associated with hormone therapy (addressed in Baker et al., 2021).

- KQ12. For transgender people, what are the effects of hormone therapy on metabolic syndrome? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

- KQ13. For transgender people, what are the effects of hormone therapy on fertility? (evaluation completed, but findings not published).

WPATH Changed SOC8 for Political Reasons

An equally serious revelation from the court documents is that WPATH made last minute changes to SOC8 as a result of political pressure. When SOC8 was first published, it included minimum ages for various hormonal and surgical procedures. Only a few days after SOC8 was published, WPATH issued a “correction notice” which dropped the age limits for all procedures except phalloplasty.

WPATH did not offer any explanation for these changes at the time but the documents disclosed in the court proceedings reveal that they were made as a result of direct pressure from the office of United States Assistant Secretary for Health and Human Services, Admiral Rachel Levine. E-mail exchanges show that Admiral Levine specifically requested WPATH to remove the age limits from SOC8 because they might be harmful to the government’s political agenda. There were also e-mail exchanges in which WPATH members consulted with “social justice” lawyers who wanted SOC8 worded in a way that would assist them in litigation over access to hormonal and surgical treatments. The Trevor project also applied pressure to remove minimum age requirements as, surprisingly, did the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

Some within WPATH had concerns about “allowing US politics to dictate international professional clinical guidelines that went through Delphi,” which was the consensus process used to arrive at final recommendation used by WPATH. WPATH, however, eventually succumbed to the pressures. This decision to prioritize politics over patient health was memorialized in the WPATH policy which stated that any evidence reviews must “positively affect the provision of transgender healthcare in the broadest sense.” The court documents suggest that the notion of “the broadest sense” incorporates WPATH’s advocacy and legal goals at the cost of adhering to the principles of evidence-based medicine.

Implications for World Health Organization

WHO has said that children and adolescents will not be included in the scope of the guideline because it concluded that “on review, the evidence base for children and adolescents is limited and variable regarding the longer-term outcomes of gender affirming care for children and adolescents.” This conclusion is consistent with the Final Report of the Cass Review. However, the suppressed evidence regarding hormones interventions for all age groups raises questions about what basis WHO is using for its presumption that hormones should be widely available to all adults who seek them, and especially young adults, who are recognized by WHO as a key vulnerable group.

WHO is an international organization which has worked hard to develop a reputation for producing trustworthy clinical guidelines. It will compromise this reputation if it continues to associate itself with WPATH, which has shown itself to be an activist organization which will manipulate evidence to achieve political goals.

In many western countries, large numbers of young people who developed gender-related distress in adolescence are now entering young adulthood. According to representative sampling of U.S. college youth, over 7 percent of US college-aged females, and over 4 percent of college-aged males identified as TGD in 2023—a more than 20-fold increase since 2013. Similar trends are found in many other countries. The Cass Review noted the similarities between the adolescent and the young adult groups’ pattern of sharply risen rates of gender-related concerns, and recommended consistent care up to age 25. This vulnerable population deserves access to treatments that are rooted in the principles of evidence-based medicine, not political activism.

Therefore, it is deeply concerning that WHO has made the decision not to evaluate the evidence for the benefits and harms of cross-sex hormones but instead to proceed with recommendations that expand access to these interventions. The new evidence that has emerged about WPATH leaves no doubt that SOC8 and its espoused positions are not a reliable starting point for the WHO guideline. Further, the WHO GDG currently includes at least 10 members of WPATH, including two former WPATH presidents who were involved in the development of SOC8 and were members of the WPATH executive when the decisions to suppress the JHU systematic reviews was made. This new information that WPATH is willing to sacrifice the principles of medical ethics and evidence-based medicine to secure political and legal victories makes the current situation untenable. There is no scenario under which the current GDG, following the currently-outlined methodology, is capable of producing a treatment guideline that will be considered trustworthy.

SEGM’s Take-Away

The Cass Review in the United Kingdom commissioned two systematic reviews of medical guidelines for gender medicine (Taylor, 2024a and 2024b) which found that WPATH SOC8 was a low quality clinical guideline. The recent US court documents shed light on the reasons behind this: it was not that the WPATH team lacked the knowledge of how to produce a trustworthy evidence-based guideline. It is that upon seeing unfavorable evidence, WPATH made the conscious choice to prioritize politics over patient health.

The U.S. court cases show alarming evidence of WPATH suppressing evidence that does not align with WPATH’s ideology that hormones and surgeries should be widely available to all who want them. The information now in the public domain paints a troubling picture: WPATH’s own treatment guidelines in SOC8 were written to be a political and legal weapon, rather than a credible treatment guideline created to improve health outcomes for TGD individuals. As a result, the WPATH SOC8 guidelines have been rendered untrustworthy.

WHO is an international organization which has worked hard to develop a reputation for producing trustworthy clinical guidelines. It will compromise this reputation if it continues to associate itself with WPATH, which has shown itself to be an activist organization which will manipulate evidence to achieve political goals.

Trans and gender diverse people are a vulnerable population which needs a trustworthy clinical guideline. The current GDG and development process are not capable of producing such a guideline. WHO needs to begin the process again with a GDG that is constituted in accordance with WHO standards for avoiding bias and conflict of interest and a process that begins with a series of properly conducted systematic reviews to evaluate the benefits and harms of cross-sex hormones as well as alternative treatments without any preconceptions.

* The court documents referenced in our letter to WHO can be found here on the SEGM website. They are also in the public domain, available to anyone registered with a PACER account.

** The status of the reviews is based on our analysis of the court documents, research protocols, and the published evidence reviews by Johns Hopkins relating to SOC8. If additional reviews exist that we may have overlooked, we will be happy to amend our analysis.

This article was originally published on the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine’s website on July 11, 2024.