Posted on 30 December 2022

by Jan Kuitenbrouwer and Peter Vasterman

Original: NRC Handelsblad – Ook transzorg moet aan medisch-wetenschappelijke standaarden voldoen

The demand for [youth] transgender care continues to soar. The use of puberty blockers – as first launched in the Netherlands – is attracting a growing barrage of international opposition. Jan Kuitenbrouwer and Peter Vasterman urge the need for independent research.

“Transgender care waiting lists too long … It destroys you,” RTL News headlined early this year. Dutch gender clinics are being overwhelmed by an almost exponential rise in demand for gender care. The previous government appointed a “Czar” to arrange a dramatic expansion in capacity. But what kind of care is needed?

In addition, more and more regretters or detransitioners are speaking out, including in the Netherlands: people who feel they were wrongly subjected to this irreversible treatment. They feel they were pushed into it and not adequately protected from themselves.

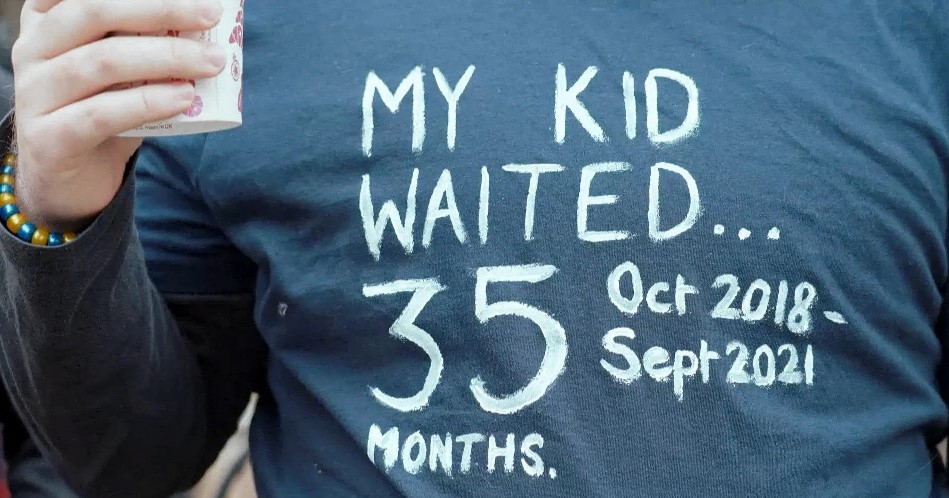

Until 2010, referrals to Dutch gender clinics averaged some 200 a year, including about 60 children and adolescents. Around 2013, numbers doubled and then rose steeply each year. In 2022, there are almost 6,000 people on the waiting list and over 5,000 in treatment, including 1,600 minors. The surge in the latter group is huge, with another 1,800 on the waiting list. These minors “do not feel at home in their own sex” and want to “transition.” This growth trend is international. The number of minors attending the UK Tavistock gender clinic has increased from 51 in 2009 to 3,585 in 2022 – with thousands more on waiting lists.

This sense of alienation from one’s sex is called “gender dysphoria” or, nowadays “gender incongruence”. Its treatment relies mainly on the administration of “cross-sex hormones”; women are given testosterone to become more “masculine” and men receive estrogen to become more “feminine.” Teenage patients are first given “puberty blockers,” drugs that arrest the physical process of puberty. In puberty, boys develop a low voice, beard growth and Adam’s apple, while girls develop breasts, wider hips, and a curvier bodies. That process is halted, the secondary sex characteristics do not develop, and the child gains time to explore their “gender identity.” Puberty blockers are called a “pause button.” If the need for transition subsides, treatment is stopped and puberty resumes, with no adverse effects. That is what is promised. If transition goes ahead, no secondary sex characteristics need to be “eliminated.”

This approach was developed in the 1990s at the gender clinic of the VU Medical Centre (now the Knowledge and Care Centre for Gender Dysphoria (KZCG) at the Amsterdam UMC). In 2006, in a study sponsored by the hormone producer Ferring, the clinic adopted strict criteria [for puberty blockers]: gender dysphoria had to be present from an early age, and to have worsened at the onset of puberty; the patient had to be psychologically stable and to be receiving sufficient emotional support. Potential side effects were played down – they were outweighed by the great benefits, consisting of relief from the torment called gender dysphoria. The approach was embraced enthusiastically, and within a few years, the “Dutch Protocol” had become the international standard of care in this field. Many tens of thousands of children worldwide are now believed to have been treated this way. In the Netherlands, estimates – official figures are not available – range from 500 to 1,000 each year.

Wanting to be something else

The leading British paediatrician Hilary Cass gave a scathing assessment of the UK’s application of the Dutch protocol and her report has led to the immediate closure of the Tavistock youth gender clinic, the largest in the world.

Today’s patients differ from those in the past. Before this “boom,” the typical “transsexual” was an adult male. Now the main increase is among young people, especially girls (75%). They are often not referred until puberty has already begun, without having reported any history of gender dysphoria. In fact, even when they arrive at the clinic they often don’t mention gender dysphoria. Rather, they claim gender incongruence – they don’t report distress so much as a desire to be something else. It is not a disorder but an “identity.” It is striking that many of these young people have additional psychological symptoms, unresolved traumas, or are struggling with their sexual orientation. One in four is on the autism spectrum. Are these symptoms the result of their dysphoria or the cause? What should be treated?

Trans organisations explain this boom as the result of society’s greater acceptance of gender diversity; doubters find it easier to “come out of the closet.” Critics point out that social acceptance of divergent behaviour is a slow process, whereas this is a very abrupt, exponential growth that began around 2013. What happened at that time? Is it a coincidence that this upsurge paralleled the spectacular growth of social media? The statistics look strikingly similar. And if this is about social acceptance, why mainly girls, when girls have traditionally been allowed more scope for gender non-conforming behaviour than boys? In addition, more and more regretters or detransitioners are speaking out, including in the Netherlands: people who feel they were wrongly subjected to this irreversible treatment. They feel they were pushed into it and not adequately protected from themselves.

In practice, it appears that puberty blockers are not a pause button for reflection but the start button for transition.

For all these reasons, the Dutch protocol is coming under growing international scrutiny. Is it the right approach for this new group? And is it really as safe and effective as was long assumed? The answers are worrying. After extensive scientific reviews of treatment, health authorities in Sweden, Finland and the UK have recently decided to prioritise psychological treatment in children from now on, and to prescribe puberty blockers only in very severe cases – or, as in Florida, to stop them altogether.

According to the Swedish review (2021), the available data do not provide sufficient evidence to properly assess the effects on gender dysphoria, psychosocial conditions, cognitive function, or physical health. “At present, the risks outweigh the potential benefits,” the Swedish healthcare authority states. The Finnish report (2020) reaches a similar conclusion, as does the UK’s [interim report from the independent] Cass Review (2022). The leading British paediatrician Hilary Cass gave a scathing assessment of the UK’s application of the Dutch protocol and her report has led to the immediate closure of the Tavistock youth gender clinic, the largest in the world.

Puberty blockers

One major concern is that puberty blockers are not in fact a “pause button” but rather a self-fulfilling prophecy. Almost all children who take them go on from puberty blockers to cross-sex hormones at age 16. In practice, it appears that puberty blockers are not a pause button for reflection but the start button for transition. The Cass Review was commissioned partly in response to the high-profile case of Keira Bell, a young woman who regrets her transition and claims to have been talked into it by the Tavistock GIDS clinic.

It is striking that while the media in neighbouring countries are reporting at length on this reconsideration of the Dutch protocol, the Dutch media are virtually silent.

More and more details are emerging of the long-term side effects of puberty blockers. These GNrHs (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormones) interfere with physical sexual development, impair bone formation (causing osteoporosis), can lead to infertility and inability to orgasm, and interfere with the ability to make rational decisions.

In addition, the scientific underpinnings of the Dutch protocol turn out to be pretty shaky. Almost all the publications relied on by the KZG team come from its own practitioners, so the researchers are simply evaluating their own work. Where are the independent studies aimed at replication? The study most often cited is that by child psychiatrist Annelou de Vries and the Amsterdam Gender Team, published in 2011 and 2014. The results supposedly show that the 55 children treated first with puberty blockers and then with cross-sex hormones reported positive results 18 months after surgery. This study has since been discredited in numerous publications, not only because of the absence of a control group and a random sample (from the total of 196 children treated) but also because of the use of two different questionnaires. Conclusion: this is not a sound evidence base.

It is therefore unsurprising that, to date, De Vries’s results have not been replicated. A research team at the Tavistock clinic made an unsuccessful attempt to do so, after which the results disappeared into a desk drawer. These results were released only recently – by order of a British court.

Head in the sand

It is striking that while the media in neighbouring countries are reporting at length on this reconsideration of the Dutch protocol, the Dutch media are virtually silent. Does the KZCG enjoy such prestige and goodwill that it is being respectfully shielded from criticism? If the Tavistock clinic worked closely with the Dutch protocol and has effectively been shut down after a review, what is going on at the Dutch clinic where this protocol was invented? And if this treatment has such a solid scientific foundation, why did De Vries recently receive NWO funding for a five-year study into the “missing evidence base”? Has irreversible, life-changing treatment been administered at the Boelelaan in Amsterdam for 20 years without an “evidence base”?

Dutch trans clinicians are burying their heads in the sand. Baudewijntje Kreukels, recently appointed as Professor of Gender and Sex Variations at the Amsterdam UMC, blamed critics in her inaugural address for “opposing … transgender care” and for finding opinions more important than scientific evidence. That’s what you call chutzpah. It is precisely the existing transgender care that would benefit from less wishful thinking and more science. This article’s writers respond precisely because they support transgender care – that is, responsible, evidence-based care.

The Netherlands was for many years the leader in this field. That status creates obligations. Before the capacity of Dutch trans care is drastically expanded, existing care must be subjected to critical, independent evaluation. The Healthcare and Youth Inspectorate must act now.

Original

NRC Handelsblad – Ook transzorg moet aan medisch-wetenschappelijke standaarden voldoen

Stella O’Malley further elaborates on this article: The Dutch Model is falling apart